An Alternative Museum of Handloom Weaving in Chanderi

An Alternative Museum of Handloom Weaving in Chanderi

Jane E Lynch

Ph.D

Wenner-Gren Foundation Grantee

On October 18, 2017, I installed a temporary pop-up exhibition in the historic weaving town of Chanderi in Madhya Pradesh. This exhibition aimed to collaboratively re-envision — and present, as a catalyst for dialogue — the ways in which the practice and process of handloom weaving are represented. Weaving is not merely a series of technical steps. As a practice and a process, it is embedded in social values, activities, and relations. In Chanderi, weaving is also inextricable from commercial transactions of yarn, cash, credit/debt, and cloth. The purpose of this exhibition was not to reject the vaildity and importance of the technical dimensions of weaving. Instead, it aimed to reveal the social and economic life from which these technical elements are often abstracted. Arguably, this perspective gives greater meaning and value to the technical expertise and shared knowledge that weaving entails.

The photographs included in this exhibition foregrounded activities that appear at first, to be either outside of or deviations from a normal course of production but are in fact, interwoven with the making of cloth. These photographs were organised according to three aspects of Chanderi weaving that are often hidden from public view and discourse: (1) the family and personal lives of weavers; (2) the organisation of business and profit; and (3) how weavers create value through the use of cast-off yarn and cloth.

Family and Home

The work of weaving in Chanderi is entwined with other aspects of social life, such as religion and kinship. As a “household industry” in which looms are fixtures in the spaces in which other domestic activities take place, weaving is not reducible to labour practices alone. Indeed, everyday activities — such as sweeping the stairs, cutting vegetables, caring for children, fixing a broken thread on a loom, bending down in prayer, and counting to see if enough cash has been saved for school fees — are interwoven with the production of cloth. Looms are the foundations of homes in which weaving is the family business. These photographs showed how the technical skill and business of weaving are learned within families, often while sitting next to a parent. They also showed how after many hours spent at looms, the looms begin to reveal traces of the weavers themselves, for example, in the stickers of political parties, cricket players, and gods stuck to their wooden frames.

Business & Profit

The production of cloth in Chanderi is a process organised not only in terms of technical steps but also in terms of financing and access to materials. The way in which business is done is rooted in both social values and expectations. One articulation of this is the principal and aspiration of shubh labh (translated in English, in the words of one trader in Chanderi, as “profit with goodness”). This group of photographs focused on the organisation of business and profit in Chanderi’s weaving industry. These images showed account books — both the ledgers kept by traders and middlemen as well as the small diaries (referred to locally as sargas) kept by weavers — that record exchanges of raw materials, finished cloth, and cash. These photographs also showed the many aspects of weaving that are unaccounted for in these ledgers, but which must nevertheless be paid for, typically by weavers.

Creating Value

Weavers in Chanderi are often left with scraps of cloth or cloth that has been rejected. Such cloth — particularly that which has been put to new use — challenges the representation of weaving as a predictable and uni-directional process with a neatly defined beginning and end. For example, one photograph showed extra material that had been woven by a woman in Chanderi into a red salwar suit, which she wore on her wedding day. Another photograph showed rejected cloth—originally woven as a curtain panel for Fab India — that had been tailored into a men’s dress shirt. Leftover cloth may also be given as gifts, used to decorate weavers’ homes, or saved for future needs. These uses of leftover cloth demonstrate how weavers find and create new value in their work.

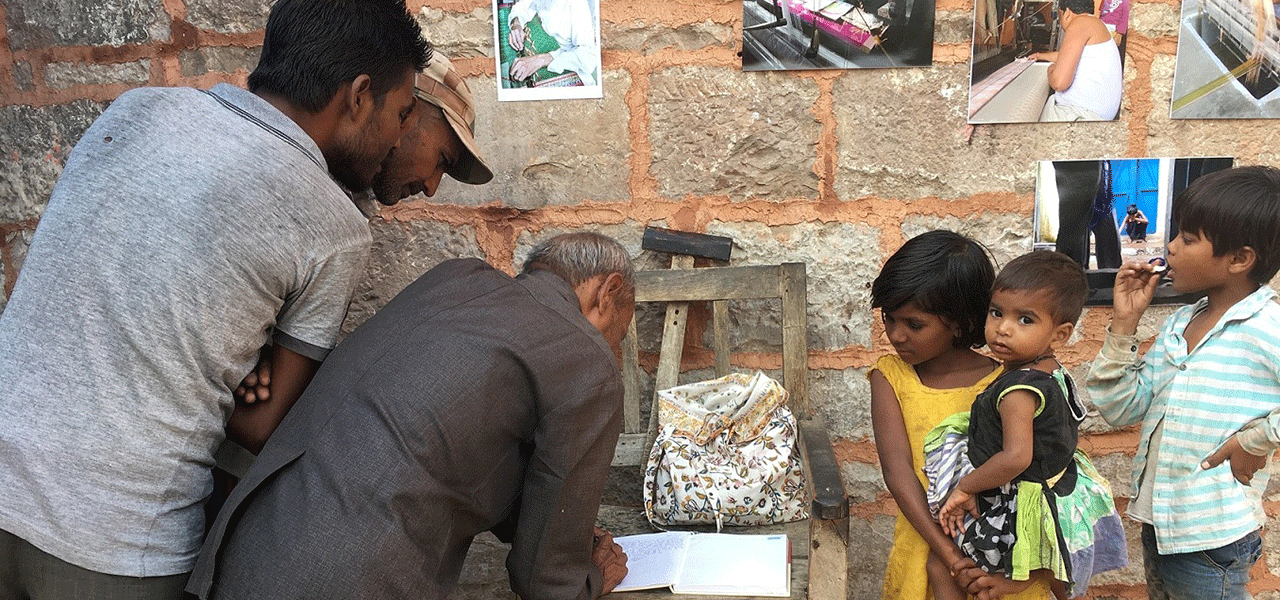

The images included in this exhibition work against conventional depictions of handloom weaving in Chanderi. And yet, they are exemplary of the kinds of things that both weavers and traders showed me during my research to explain their work, their claims about the challenges and possibilities of handloom weaving, and their insistence on what was at stake in all of this. In order to collaboratively re-envision and represent the practice and process of weaving, this project invited weavers and others in Chanderi to participate in this project. The temporary exhibition was organized so that could be accessed freely. Instead of exhibiting the photographs in a private, interior space, we instead used an accessible, public space—the walls beside Dholiya Darwaza, the main entrance to Sadaar Bazaar — in order to accomodate spontaneous experiences of viewing, discussion, and engagement. The exhibition was intended to create dialogue and all visitors were invited to ask questions, share their thoughts, and write down their reactions as part of the formal record from the event.

The event was covered in the local news media, Dainik Bhaskar. Working together with the Delhi-based organisation Sahapedia, I also plan to document the exhibition and create a digitial catalogue that can be accessed online by the public. Together with the exhibition itself, the aim of this digital catalogue of the event is to encourage new public discourses on and policies with respect to the handloom weaving industry in India and the communities in which weaving is practiced. By bringing the diverse perspectives of weavers to the foreground, this project also seeks to help cultivate more equitable and inclusive conversations about the stakes and significance of handloom weaving.

Background

This project is an outgrowth of my dissertation research, substantial parts of which were conducted in Chanderi. The photographs included in this exhibition were taken over a period of six years, 2011-2017. Most of the images date to 2011-2012, when I was in Chanderi for an extended period, conducting research for my Ph.D dissertation. This dissertation, titled The Good of Cloth: Bringing Ethics to Market in India’s Handloom Textile Industry, examined efforts to revitalise and do business in the handloom textile industry in India. In this study, I was particularly interested in the nature and negotiation of “value” and “ethics” in commercial transactions and relationships. Over the course of 22 months, I traveled across India to meet with government officials, artisans, fashion designers, social reformers, heads of companies, and traders. I asked when and why cloth is taken to be fundamentally “good,” and how that goodness translates into profit. My research conducted in Chanderi and elsewhere in India reveals that the goodness of goods is neither given, nor epiphenomenal. Goodness, I argue, is interactive and transactional. In other words, ethical values are not fixed. They are created and contested through transactions that take place in the traders’ shops, in account ledgers, during shareholder meetings, through tax law, in weavers’ homes, and at the looms.

For more information, please contact Jane E. Lynch, Ph.D. at jelynch@umich.edu

This project was funded by Engaged Anthropology Grant from the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. I am grateful to the help and support of the Digital Empowerment Foundation and Sahapedia as well as friends and collaborators in Chanderi, especially Muzaffar Ansari. Thank you also to the many people in Chanderi who shared their perspectives, stories, and knowledge with me during my research.