By Sarah Farooqui

By Sarah Farooqui

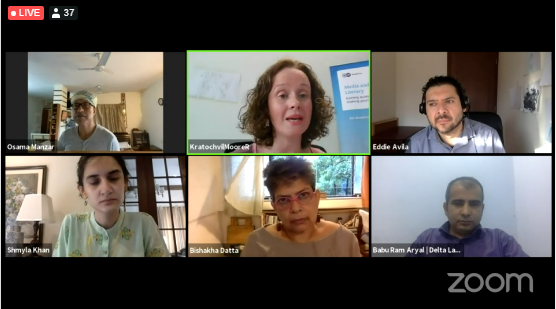

On 30 July, participants from Germany, India, Bolivia, Nepal and Pakistan took part in a digital RightsCon 2020 panel to bring perspectives from around the world to the topic of empowering citizens through media and information literacy. Each of the panellists highlighted their methods for dealing with misinformation in their own local context and professional experience. The session was moderated by Osama Manzar, director of the India-based Digital Empowerment Foundation (DEF), who explained the purpose of the session, which focused on media information literacy, fake news, disinformation, regulations around the subject, and how one is affected by it, particularly during COVID-19.

Roslyn Kratochvil-Moore, manager of the Media and Information Literacy Project at DW Akademie in Germany, emphasised the increase in smart phones and internet access, as well as the increase in the quantity of information being circulated. Often the audience is unable to identify the types of messages and information coming from reliable or trusted sources and differentiate between what is false, misleading, or satire. This was the reason she focused on media systems and development and looked at the audience and users in order to ensure that the media stays viable and vital as an information source. Kratochvil-Moore has been developing media literacy through projects and explained how this was about individual competence in understanding media messages, as well as people knowing and claiming their rights.

Bishakha Datta, executive director of Point of View, India, explained how misinformation, fake news, and the lack of regulation was a global problem, and how it takes a different shape in different parts of the world. In India, disinformation, misinformation and fake news are strongly linked to WhatsApp. She elucidated this point with an example of a WhatsApp message with fake news, where somebody deliberately deemed an individual dead in the context of religious tensions. This instance revealed the power of fake news, where an individual is believed dead even while standing in front of authorities. Datta also touched upon the kinds of fake news that predominate in India, which include those related to coronavirus, claims about Muslim minorities and discriminatory acts.

Osama Manzar expanded upon the types of misinformation currently circulating and how citizens suffer because of the “manufacturing units” that produce fake news that is manipulated to align with the biases and beliefs of the people rather than inform them. “The less educated the community and society, the more it touches on your emotion and belief system, biases, and prejudices.”

Shmyla Khan, project manager for the Digital Rights Foundation in Pakistan, shed light on Pakistan’s opposition to media and information literacy and a lack of freedom of speech. Khan mentioned the history and context, explaining that there is a lack of trust in any information coming from authorities. “It creates an interesting dynamic and it does play out in the same way as it does in India,” she said. “Not only has it led to physical violence, but there are regular coordinated campaigns with specific aims of maligning someone. If a journalist is explicitly critiquing someone, you will see a coordinated campaign against them.”

Khan went on to clarify how certain laws have been misused, particularly those governing online spaces. “It is being weaponised politically by authorities, who in the ideal situation should be looking for a tool for accurate information. The complication here is that within the information landscape you don’t know who is an authority and who is telling the truth.” With the pandemic and increased internet usage, she emphasised the number of new people entering the digital economy and explained how it had exacerbated knowledge gaps and misinformation regarding public health, including governmentally distributed content. There were no clear markers showing consumers what is true versus what is false, and no explanations of the spread of disinformation in Pakistan.

Eddie Avila, the director of the Global Voices initiative Rising Voices, who is based in Bolivia, spoke about his experiences and what must be learned in an era of information overload, and how misinformation and fake news can be countered.

“Over the last nine months we have seen many challenges and seeing this play out in real time has been on the job training.” He expanded on how the pandemic has allowed misinformation to spread and be shared across neighbourhoods, WhatsApp groups, in places where one would normally not expect to find it. Psychological stress, the need for information in desperate times and worry have factored into how people respond to what they read.

Avila also spoke on the role of trust and the idea of trust being relative. He explained, “Trust for one person may not be trust for another person.” He also highlighted the different reasons why people share misinformation. “People are not trying to disinform, but because of fear or worry they share misinformation.” He also noted that the problem of fake news and misinformation was so deep, one could not pinpoint whether it was a behavioural problem or a technology-related problem.

Babu Ram Aryal, chief executive officer at Delta Law Private Limited, Nepal, explained how fake news and misinformation have impacted Nepal. He explained the role of mainstream media, with examples of two versions of the newspaper Kantipur, the original version and the fake version, which run different news stories. This has had a big impact across Nepal. He also spoke to the role of governments and ministries in different contexts, which have participated in the spreading of misinformation. Aryal also commented on how legislative reforms had been used in Nepal, where the government has taken legislative action and implemented reforms to curb media outlets and regulate digital media, and the implications on the broader discourse with respect to misinformation.

On regulations

Kratochvil-Moore highlighted the contradictions which come with legislation to curb misinformation and fake news. She explained how various countries have taken the opportunity to legislate telecommunications platforms using cybercrime and anti-terrorism laws, which was not the kind of regulation needed and has shut down freedom of expression and civil liberties. She also pointed out the fact that some of these regulations took place in liberal democracies, which was not expected. “What kind of regulation do we want or need?” she asked. “We need media and information literacy and we have to work with communities and organisations in the short term, and in the medium term get education ministries to mainstream media and information literacy into the education curriculum, which is difficult to change, and there is no political push for it.” She further explained that this is part of a bigger process and governments need to hold social media companies accountable and challenge the business models that manufacture fake news, and regulate against them, not the individuals spreading the content.

Datta, for her part, warned of the dangers of giving up internet rights in the name of combating fake news. She explained that the difficulty in asking for new legislation is that governments will use it as an opportunity to ask for encryption standards to be removed or lessened in the name of disinformation and misinformation. “We know there has been a proposal to introduce traceability – where did the message originate? This is a dangerous path, to give up internet rights to combat fake news.” She clarified that there is not one solution, and it will require media literacy, some regulation, and pushing intermediaries to take a strong stand. She explained how people are suffering from the impacts of “units of information” aligned to their biases and beliefs, which often have little to do with reality. The evidence of this, she said, was particularly strong in communities and societies which are less educated.

What are the solutions going forward?

Speaking on the nature of the solutions needed, Eddie Avila pointed to another factor, which is the economic viability of the media through the pandemic. “Newspapers in Bolivia are letting people go, top journalists are leaving because of uncertainty, and that is causing polarity of media information,” he explained. “The solution is complex, but we can’t raise our hands and give up. We need to find small ways to help people better understand that this is a critical skill people need – to be critical about the information they consume.”

Babu Ram Aryal said that from a regulatory perspective, fewer laws and regulations would lead to fewer problems. According to him, rather than using legislation, introducing academic courses with social media in the curriculum would be a better way forward. Journalists, researchers and social rights contributors can also disseminate reliable information. The mainstream solution would respect government structure but would also introduce content and approaches to tackle fake news and its impact, which could be significant.

Khan highlighted the negatives of adding any regulation of misinformation that could be used to control media spaces and regulations for user protection. This could specifically give leverage to citizen petition bodies that can adjudicate on many things, including fake news, but without any clear definition of what it constitutes. She explained how media information literacy is seen as different from technology and digital literacy and there is a lack of a multidisciplinary approach. A lot of this is grounded in sociological and psychological factors and the human element cannot be taken away, especially in communities under constant threat of state surveillance and violence. She also spoke about the need to be creative with media and the approaches used to tackle misinformation.

Osama Manzar concluded the session by summarising how misinformation affects lives and how social media has emerged as one of the biggest disseminators of misinformation. He added that political powers are taking advantage of misinformation and fake news and not doing nearly enough to counter its effects. Manzar concluded by saying that there is a need for media information literacy at a mass scale, creating communities and building a community of trust. “This need has been evident throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, as we understand that our localised community is very important and can only be built on a foundation of trusted information, knowledge and wisdom,” he stressed.

This article was published on Associate for Progressive Communications website on August 19, 2020. Sara Farooqui is the Research and Advocacy Manager at Digital Empowerment Foundation.

Link to the article: https://www.apc.org/en/blog/between-regulation-and-rights-def-rightscon