This article was first published in the Mint newspaper on October 23, 2017.

Last month I read an interesting article about India’s postmen. It talked about the changing duties of postmen and the changing role of post offices. By the end of the article I was thinking of a scenario where our close to 2 lakh post offices are connected to the internet. I was excited.

I was compelled to find out what’s happening in the villages where Digital Empowerment Foundation works. I immediately opened a WhatsApp group and asked some of our ground staff to interview their local postman on camera.

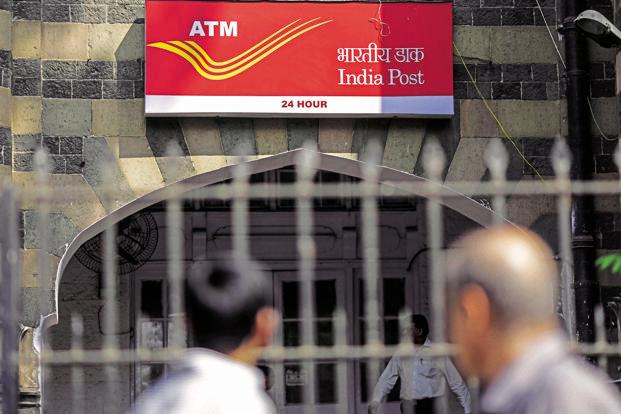

For those who are not aware, a post office is not just a space where mail is received and despatched, it is also a public institution that acts as a bank. It facilitates money orders, allows people to open post office savings accounts, and provides people with access to various life insurance and other government schemes.

Over the next couple of weeks, we received 22 videos from Assam, Meghalaya, Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand and Rajasthan. A few things were common across all post offices. The kind of mail received or despatched had changed. Earlier, people exchanged a lot of letters with their loved ones; many of them had to be written by the postmen themselves. “Today, everyone has a mobile phone; they simply call” is what a number of Gramin Dak Sevaks said. “There was a time when we felt tired just drafting letters for people and delivering them every day. Today, I’m delivering no more than 20 to 30 letters in a week,” Basant Lal, a 33-year-old postman told our ground staff in Barabanki, Uttar Pradesh. Most mail today comprises either letters or documents from the government or from educational institutions. “Delivery of Aadhaar and PAN cards is most common today. Almost nobody writes personal letters anymore,” he added.

While administrative responsibilities of post offices have increased with the increasing number of schemes and services offered, mobile phones have made things a little easier.

Munni Bai Soni, the 56-year-old postmaster in Deshawadi, Madhya Pradesh, said, “Sometimes, when we don’t have enough mail to deliver in a village or if a parcel is too big, we call the recipients to tell them that they can collect it from the post office.”

The postman in Kachcha panchayat of Madhya Pradesh, Dilip Kumar, feels unproductive work has reduced with increasing penetration of mobile phones. “Not a lot of people come to us anymore to seek information about government or insurance schemes. Young boys and girls are tech savvy, and quickly look up the details online.”

What about them? Can they also look up information immediately on the internet? No. Out of the 22 post offices we spoke to, only four had a functional internet connection. Most others have been “promised internet soon”, but it’s been a couple of years since the promise was made. Among the staff at the 22 post offices, only three had smartphones. Of the three, one had no data pack because there is no internet connectivity in his village.

Narayan Prasad, a postman stationed in Assam, covers a radius of about 40-45km. He no longer needs to go around every day delivering mail and then come back to the post office to do the paper work. The department has given him a 4G-enabled smartphone that is synced to his computer. “Whatever I feed on my phone application is transferred to my computer automatically. All my deliveries are recorded instantly,” he says.

A postman in Ranchi is particularly happy with the internet. It has made it easy for him to access government information and updates in real time, send information to the district office or reports to the Department of Posts. There is no need to manually log entries. However, the post office in Tehri, Uttarakhand, is yet to reap the benefits of the internet. The postmaster there is yet to learn how to use a computer.

India has the largest postal network in the world with over 154,882 post offices, of which 89.86% are in rural areas. While all of them are supposed to have an internet connection (and be digitized by the end of the year), internet connectivity is non-functional at hundreds and thousands of post offices. The government-operated institution employs over 6 lakh people, and offers a range of mail and monetary exchange facilities. With such a wide network—each post office is meant to serve an area of about 20 square kilometers—it would be ideal for the post offices to have access to broadband internet connectivity and functional mobile/digital literacy to not just carry out traditional services offered at a post office but transform into digitally-enabled entitlements’ offices.

This way, every post office will act as a government centre for the last mile, providing citizens with information on various government schemes and entitlements, and enabling access to the same by allowing download of relevant application forms for schemes, assisting rural communities in filling up the forms and submitting the forms online on behalf of the beneficiaries.

So can all post masters be trained in functional digital literacy? Can all post offices become hubs of digital services such as printing, scanning and copying? Since the post offices are the last-mile access for most villages, it will save villagers the money and time that they would otherwise expend to travel to the nearest block to access these services.

As I write this column on World Post Day (9 October), I wonder if by the next World Post Day we would have more to celebrate about our post offices than just new stamps.