This article was first published by the Mint newspaper on April 6, 2017.

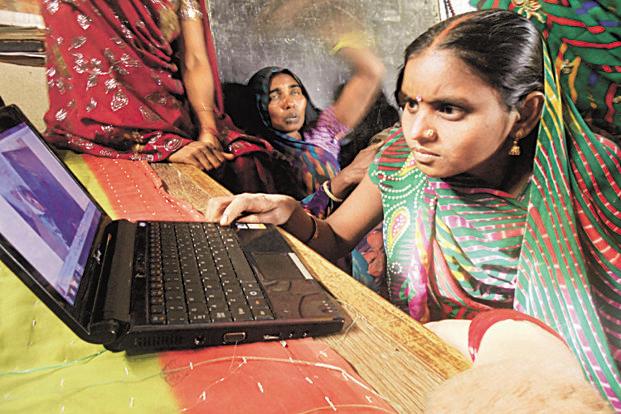

We have been engaged in the area of digital literacy for the past 15 years. However, we haven’t solely been working with the perspective of creating ‘digitally literate individuals’. We’re continuously working on the ground to experiment on how digital interventions can enhance the lives of people. We are determined to transform the information poor into information rich, and enable marginalized and underserved communities to become part of the interactive economy.

The government, too, is trying hard to push digital adoption and penetration. In this effort, we’ve seen hundreds and thousands of curriculums being developed for digital literacy, and now financial digital literacy as well. The education sector, particularly, is gung-ho on its agenda to make people digitally literate so that they can consume information and services being offered by the government online. In fact, the government-driven National Digital Literacy Mission (NDLM) programme, of which we have been a part, is aimed at creating digitally literate individuals. Last year, they raised their goal to target 60 million additional (previous target was 4 million) individuals under the scheme. When NDLM was being planned and was in its nascent stages, there was a lot of deliberation and discussion on how to develop a curriculum that best suits the needs and learning capacities of rural populations. Following the planning of a course structure, it was decided that each NDLM trainee will have to go through an examination at the end of the course to truly qualify as a ‘digitally literate’ person.

Now, the project is struggling to make the curriculum certificate-oriented. But our experience on the ground has taught us that you don’t really need a rigid curriculum. All you have to do is expose people to digital as a medium and let them explore it on their own. We’ve seen some amazing results come out of this experiment.

By simply giving access to technology and basic knowledge of operating a device we have tried to understand what rural India is exploring online. The results are wide and varied. In a rural location near Puducherry, a group of girls are accessing the Internet to take ‘How to become a beautician’ course on YouTube. Children in rural Alwar, Rajasthan, who have never travelled outside their village, are looking up the Charminar in Hyderabad online. A woman from a Bengaluru slum likes to learn from make-up tutorials online. A man in Tekulodu, Andhra Pradesh, is learning about organic farming to make his land sustainable and profitable. A couple of men in Erumad, Tamil Nadu, are reading up about tribal rights so that they can better serve their community. A young woman in Musiri, Tamil Nadu, is learning how to design cotton sarees to fight competition. None of them had been taught to look for anything in particular. Instead, they were given the freedom to look up whatever they wanted to.

Do you think digital literacy is a means to consume diverse content for rural Indians? If you believe that, do you think we’re producing enough relevant and contextual content for them? Are we really providing ‘digital’ as a platform that enables them to create their own content and offer services? There are various news portals today that want to share rural news but are they catering to the needs of the rural population or are they simply satisfied to serve the English-reading Internet-enabled urban population of India? Is the centre making a right policy by encouraging the rural population to go online without creating relevant contextual content for them to access?

I want to make three recommendations. Firstly, the so-called content creators and access facilitators need to push any stereotype that they might have in their heads regarding what rural consumers would like to do online. When given access to the Internet, the rural population might be looking for things as diverse as what the urban population is looking for, or probably even more diverse that we can imagine. Secondly, those offering digital literacy courses to the rural population should see it as a means of not just enabling the digital immigrants to become consumers of information available online but also producers of content available online. Thirdly, the government and civil society’s approach towards digital literacy should not be to meet target and throw numbers of making a certain number of individuals digitally literate but to ensure that the same number of people continue to use the training provided to them for the purpose they want to use it for.

About 70% of India lives in rural areas. They not only constitute a large population of potential consumers of information online but they also hold hundreds of years of experience, knowledge and wisdom—tried, tested and preserved—across areas such as agriculture, soil, art, culture, language, design, handicraft, architecture, food, medicine, education, history, trade, water conservation, environment protection, love and empathy, among others. Unless we treat this large unconnected population as a pool of producers (rather than serving it with content that our judgement says suits them best), we will not be able to achieve the results we dream in a Digital India.